and Wolfgang Pape (CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies, Bruxelles).

Source: Rohman Obet.

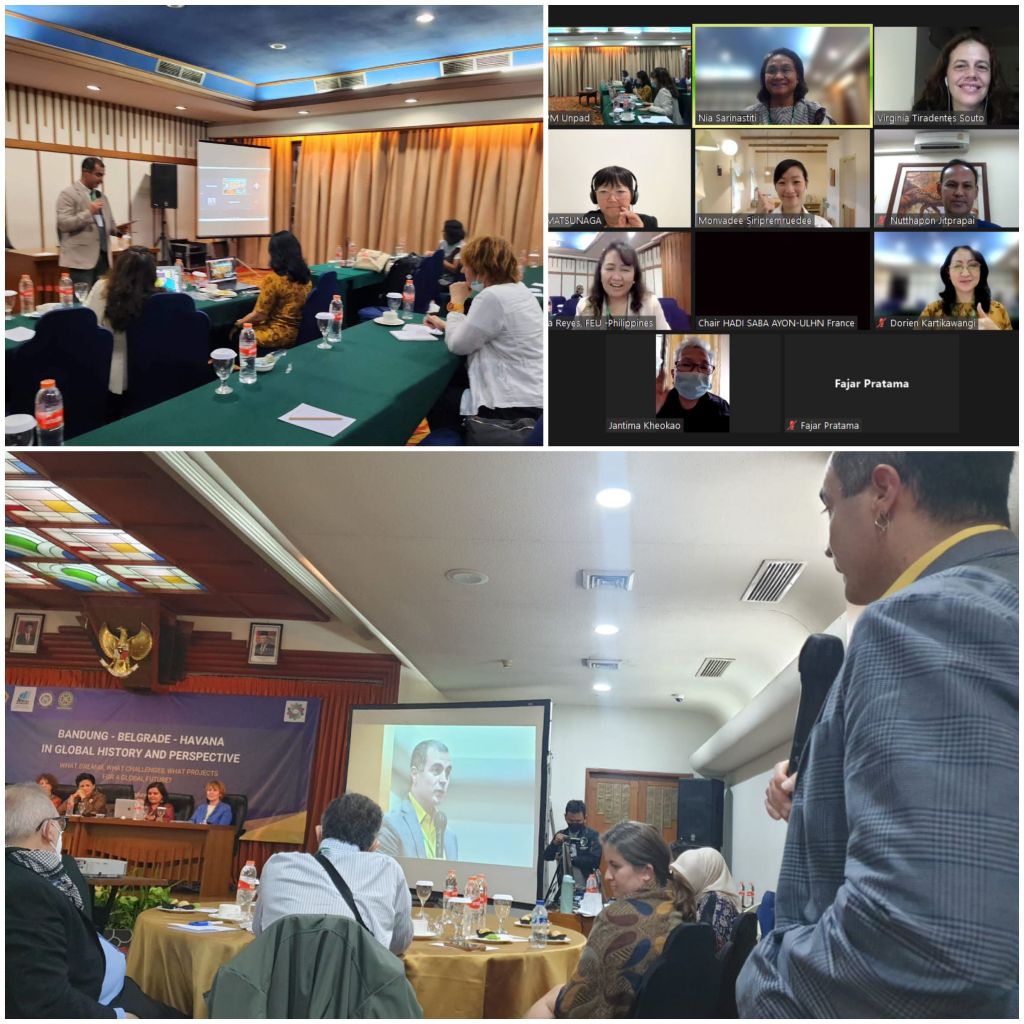

This intervention occurred in a plenary session at Bandung – Belgrade – Havana International Conference at Airlangga University in Surabaya – Indonesia, on 11 November 2022.

The title of our session, “Digital Transformation towards a New Civilization”, evokes several questions about the digital as a milieu/a civilization/a “new religion”, dare I say, and the transformations that its culture introduces in our lives. It reminds me of the French sociologist Dominique Cardon (2019), who writes in his book Culture numérique the following:

“It is important to have varied and interdisciplinary knowledge to live with agility and caution (in a new world that digital enriches, transforms and monitors) because if we fabricate digital, digital also fabricates us”.

It leads us to think about the problems of our calculation society that encompasses connections between machines and the human being in its three versions:

- A Human-trace (Ichnos Anthropos): who is a product and a producer of traces (especially of digital traces in this context);

- A Homo economicus (Omo Oikonomikos): the human as a market actor;

- and a Homo politicus (Oikonomikós Anthropos): a political animal intended to live in a polis, a city.

Digital has established itself as a new culture-changing our relationship to space, politics, things and ourselves. These transformations come from the interaction between intelligent machines (computers, then artificial intelligence) and users in innumerable fields and domains. These transformations became dynamics that characterized human society, turning it into an algorithmic society driven by a computing infrastructure. In this extensive environment/system (built from multiple layers), humans and machines are set up together – where our clicks, conversations, purchases, bodies, finances, and sleep become calculable data – a “new civilization” arises. The civilization of the Internet is known as the digital era. However, the Internet is not abstract. It is an object with a body, a language based on scientific operations, that generates new entities (digital traces) that restructure our reality. Furthermore, the most important is that it has a history. Moreover, this history interests us in analyzing and understanding so that we can deconstruct and adjust this civilization process.

The history of the Internet led us to search the history of old civilizations about common elements and contradictions that help us understand the mutations we are witnessing in our present. A comparative analysis between the Internet and Phoenicia seems essential to us. What relation can we find between an information and communication network and a model of urban city-states on the Mediterranean coast that existed more than three thousand years ago?

In a brief explication that we will develop later in a presentation in another session, we can say that there are three intriguing aspects to be discussed:

- The Internet has a body. It started as a public-military project before being privatized. Phoenician city-states experimented with the transition from a political and economic power from the royal palaces to a mercantile class.

- The Internet has a universal language that allows anyone to connect and use. Phoenicians invented alphabetical writing that was accessible to all, and thanks to it, Phoenicia got its political entity.

- The Internet is in crisis because of the privatization process that gave private firms the right to manage their actions for profit while neglecting the rights and needs of users. Phoenicia, characterized by trade activities, could not survive as a civilization and did not become a model of democracy and citizenship.

Talking about/remembering Phoenicia from a historical point of view concerning the Internet has a linkage to memory. Memory is the process of mobilizing resources, which aims less at restitution’s exactness than regeneration (Merzeau, 2017). Sharing a memory is not limited to this often interesting production of heritage objects disconnected from all social ties. It consists less of recording, storing or preserving traces than of embedding them in a common framework — whether a place, a rite, a device or a story. In our case, it is a study/analysis for a scientific purpose. Here, saying a word about memory in the digital context is essential.

Louise Merzeau, a French Professor and researcher from Paris 10 University who left us in 2017, and I had the honour to work with her for several years, demonstrates that the digital culture has introduced an anthropological mutation concerning memory. She writes that until the advent of the digital (le numérique), the fight against oblivion required an actual deployment of energy, tools and technological innovations. In other words, investing in archiving, preserving and building memories is needed digitally. It has introduced a break, even a reversal of this process: communication, production, registration and sharing systems via networks or digital media have generated automatic traceability, a condition of our activities and, therefore, before any real intention to “make a trace”. Today all efforts, technological means, knowledge and policies must no longer be used to memorize in traditional ways but to regulate oblivion, as the Internet is a kind of auto-memory, which is, in reality, an anti-memory. So the individual or the community decides what it wishes to transmit or, on the contrary, to erase. Moreover, as there is no memory without a thought of oblivion, it is therefore imperative to rethink oblivion collectively to regulate it and structure it so that it makes sense.

However, the Internet privatized does not give an option to its users to do that. That is why, getting back to our comparative analysis between the Internet and Phoenicia, we back the emergence of two proposals, one concerns the upper level of the Internet (what to do on the platforms), and the other is related to the lower level of the Network:

- As digital writing is exhibiting new traces while pushing back others to be forgotten, the first suggestion is to transform our interaction in the digital into participation by developing individual or collective digital cultural memories. Our digital traces are removed from their contexts and scattered in the networks. They are alimenting the Big Data and used by private firms to make money. When we appropriate these traces in memory projects, they become commons, a part of a heritage policy that raises issues of knowledge. In this direction, we ensure a transition in the status of the digital user, from homo econimicus to homo politicus, from a market actor to a citizen/netizen (digital citizen) who has control over decisions with self-determination in the digital environment as well as in the social life.

- The second proposal seeks the basement of the Internet. Let us not forget that the Internet is first made of pipes. Everything we do up the stack depends on these pipes working correctly. What if users and communities manage to hijack the privatization of the pipes and the monopoly of the Telecom companies and start creating their networks with the support of Public institutions with technical expertise and infrastructure? The purpose is to establish an Internet managed by community networks, an Internet that “places people over the profit”, as Ben Tarnoff (2022) says. In his Book Internet for the People: The Fight for Our Digital Future, Tarnoff writes, “The internet is not just material and historical, then; it is also political”. In this sense, our proposal is political, can bring people into new relationships of trust and solidarity, and encourages caring for collective infrastructure and one another.

Thank you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.